SYNTHESIS

Facts and Trends

After so many trips to the countries involved, a global synthesis must be attempted:

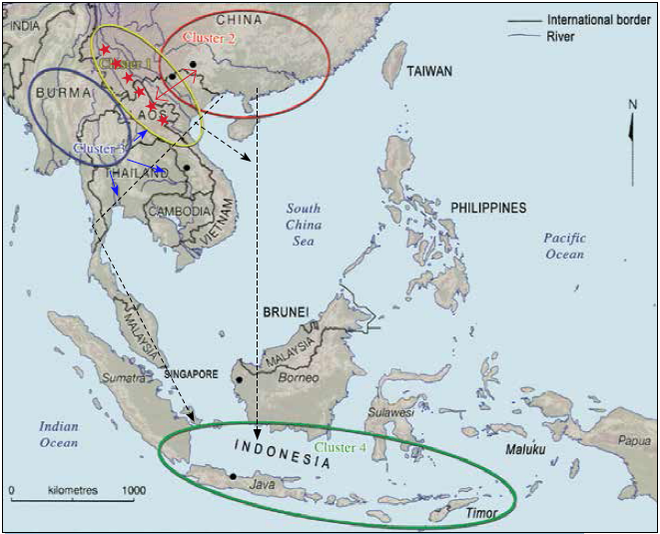

- Around 500 BCE, bronze drums were invented in independent Kingdom(s) around the extinguished area of the Red River basin covering the future (Chinese) Yunnan and (Vietnamese) Tonkin, including Dian culture at north and Đông Sơn at south. Bronze drums precise origins are always discussed but they crowned a large ceremonial family of bronze items. They were nicely developed under different formats of which the “mushroom” type (Heger I) played a key part with specific ways of decoration and uses, soon relayed by the more rustic but bigger Heger II not for getting the smaller Heger IV. As a result a Cluster1could be defined covering that enlarged basin. Guangxi with eastern new colonized Chinese provinces took up the baton, inspired by its western and southern neighbors Yunnan and Giao Chi (Tonkin). From beginning CE was developed over centuries an enlarged branch of bronze drums, so nice and numerous to make a Cluster Corresponding drums were largely exported via active pre-existing ways of trade, terrestrial and maritime, to all Indochina peninsula and down to southern Archipelagos. So successfully that both clusters (1+2) gave birth to a kind of Bronze Drums’ Golden Age at all latitudes of South-East Asia at the verge of BCE/CE.

- Later in Burma, from the middle of the first millenary CE, Karen came from the north (China) and created a new type of bronze drums (Heger III), partly inspired by the precedents. More homogeneous and middle sized, with aquatic decorations of which the emblematic frogs, they were made by the metallurgist (and Buddhist) Shan till the twentieth century CE. From a minuscule Karenni (Red Karen) territory lost in the eastern mountains (Red Karen, future Kayah) Heger III drums “peacefully invaded” next Lao territories, and soon most Indochinese markets but never the Archipelagos. Becoming Cluster 3 in the great drums’ history.

- Far away, in Java and Bali, a very new “hourglass-type” drums’ family was invented during the first millenary CE, quite revolutionary albeit inspired by northern imported drums. So-called Pejeng and Moko, only the last ones being still alive, these drums corresponded to a Cluster 4 of success, although local and modest compared with the precedents.

These four clusters (1 to 4) cannot be compared with a motor, the discontinuities being too large, but these rebounds covering more than two thousand years are impressive. Even if a lot of mysteries subsist with many different and sometimes contradictory interpretations. Modestly, it will be tempted to enlighten them with any new suggestions.

Tentative interpretations

Bronze drums didn’t came from scratch

The temptation was probably general to try to “metallize” all the existing objects first made in basic materials: to go from stone or wood to copper and bronze, before iron Age. Drums have existed for a long time everywhere in the world, generally made locally in bamboo wood offering a good resonance case easy to cover with any skin or material. Once made in bronze, they will be part of a sophisticated upper ceremonial family including “situla” (vases), bells, gongs, all more or less similarly adorned and apt to musical usages from birth to funeral.

Before to be built properly as bronze drums, traces suggested that they possibly emerged from domestic kettle(s) on the bottom of which musical sounds were first emitted with hands or mallet to rhythm songs or dances. At origins may be a basic bronze kettle of the house was good enough to be played before to be ulteriorly decorated and shaped to become “pure” drum resembling with a stronger musicality to the earlier wooden ones created and played for long.

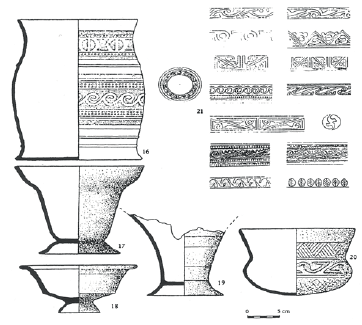

Last important precedent: coming after the neolithic age bronze drums’ creation benefitted from the previous discoveries. First for their casting based on high temperature processes already initiated for ceramic production and quickly improved but also for their decoration if we consider the inspiring curvilinear and rectangular patterns; for example, the attested links between Phung Nguyen pottery and Đông Sơn bronze cultures in future Vietnam.

Preceding Ceramic cultures influenced directly Bronze Drum decoration

Phung Nguyen culture covered from 3500 BCE period in relation with a first wealthy sedentary phase of rice cultivation with new techniques coming from central China when were also introduced the first bronze artefacts (axes; arrows; etc). Đông Dau (from 2500 BCE) and Go Mun ceramic cultures took the baton until (future) Yunnan in the north and Đông Sơn (from 1500 CE) in the south created Bronze Drums around 500 BCE. In parallel of a coming Iron Age. (Experts recently lowered their dates)

The links are evident, even if not fully explained, with the future bronze drums geometric decoration – issued probably from agrarian and watered backgrounds corresponding to the rice revolution. (Fig. 2). It means that most of the (possible) explanations concerning geometric decoration sources on bronze drums must be researched much earlier, during the second millenary BCE. Of course these remarks about Phung Nguyen could be extended to all the pre-existing neolithic ceramic cultures of the entire drum’s area.

About bronze drums’ rise

Bronze appeared to be an outstanding material for drums, adding to their wooden predecessors more sonority and strength, no more perishable and ready to receive all types of permanent decoration, giving a possible image of eternity for believers, being a sign of wealth and power for all. With their sophistication at the end of BCE, they became probably “deluxe products” first accessible to rich clienteles, not necessarily devotees, able to buy so beautiful but costly creations. Their rise probably coincided with a lot positive feedbacks between northern Dianchi Lake and southern Ma River via the Red River Valley; the distances in between are relatively short and the best artists could be mobile along that basic axis defined as Cluster 1.

In the north, the rustic and probably pioneer Wanjiaba drum type soon benefited from the gorgeous cowrie-shells creations of Dian Kings buried in Shizhaishan. Possibly in parallel, but probably in conjunction, the southern habitat of Au Lac also produced sophisticated models mostly called Đông Sơn in (future) Tonkin (Vietnam).

Several Heger I from Đông Sơn had been found in Dian tombs and reciprocally few Dian Heger I and IV reached Au Lac area. Until now no-one was able to prove any leadership along such enlarged Red River basin: better to speak of multiple “joint-venture” or “win/win” bronze drums exchanges between the numerous independent kingdoms forming the region before the arrival of Western Han northern invaders.

A new “drum culture” was born and developed, soon invading Guangxi and around at north, all the Indochina Peninsula, and the southern Archipelagos.

About the decline of the early bronze drums

At least two main aspects explained that decline, apart the tiresome course of time.

- The encroaching Han Empire colonization slowed down old local cultures.

- The absence of relays in other powerful regions of Asia

Concerning first China, Buddhism reached its Empire during the first century CE when precisely Han finished to colonise the southern people and were not inclined to accept their “barbarian” southern innovations in supplement.

Concerning the not so far India, its pre-existing two major Hindu and Buddhist cults leaved no place for further temptations of backing animism. On the contrary from the middle of the first millenary ce these beliefs invade Indochina and soon inspired the local casting of bronze statues in Angkor where no trace of bronze drums existed among the so rich decorations of its walls. The imported cults replaced at once old animist beliefs and their instruments-both collateral victims of the so-called “Indianization”.

A fortiori far away Japan under ancestral Shinto rules, so autonomous without external relations at the BCE/CE stage, was never reached by the “bronze drum phenomena” even if several early specimen are now displayed in the Tokyo National Museum. By contrast the (future) Philippines, northern part of Archipelagos and early hub for maritime routes might have been concerned, pending possible bronze drums findings.

About bronze drums unexpected rebounds

- Chinese Guangxi and its near provinces (Cluster 2) remained a spectacular exception in the early bronze drums declining trends. It probably corresponded to the existence of a majority of other “Nationalities” in front of the central Han power, and also to direct maritime fluxes of exchanges with the pre-existing southern customers. So was guaranteed the perenity of the drums, appreciated gifts or valuable booty as historically attested during the successive coming dynasties of the Tang, Song, Ming, Quing before 21st century drums’ festivals.

- Karenni second bronze drums rebound in Burma looks like a kind of miracle with new formats invented by a minuscule tribe long time itinerant but instructed along clusters 1 and/or 2. Their Heger III beautiful qualities were certainly keys of their success but we must also underline the role played by the Shan in charge of their coating if not their marketing. Buddhist Shan, second by population and richest Nationality in Burma, gave to Karenni drums better chances to emerge as Cluster 3 till the 20th century CE.

- Indonesian Pejeng and Moko Cluster 4 look like a more classical rebound in Arts history. From an imported flux of far away bronze drums’ masterpieces, local people were able to understand their concepts and learned at once the ways of casting. After a while they adapted them to their tastes and needs as, for example, did in Europe French or German peoples creating new styles inspired by Rome. Moko’s survival is proving their vitality.

About bronze drums’ global interpretations (non exhaustive)

- For Frantz Heger describing the “Moulié” drum, scenes with reproduction of houses, feathered men, boats, flying birds, attested to “local inauguration”.

- For Henri Parmentier drums’ decoration gave a general description of the local life, as the “Achilles Buckler” did for ancient Greece.

- For Victor Goloubew, decorations might be a representation of funeral ceremonies for “souls’ survival” with golden boats and birds opening the skies for the deceased. Moulié drum, before its acquisition, was used during funerals.

- For Madeleine Colani, Đông Sơn drums’ decorations resulted possibly from specific cults to the “Polar Star”, so important in archipelagos, and shaman’s magic relations with the sky.

- For E. Porée Maspéro, bronze drums decorations were in permanent relation with “Deluge myths” and battles between totemic genius of draught and rains but never related to funeral rites.

We could multiply the references from the best western or eastern scholars, each of them favouring one or two hypothesis, often contradictory, without any clear proof. It must be a lesson of humility for all of us.

However it can be tempted to list the main functions assumed by Bronze Drums if we consider at once the information given by old Chinese texts and modern missionaries. Each function being eventually considered at two levels, a first degree “visible” and a second degree “invisible”, for devotees only, the following list is suggested by decreasing order of importance by reference to the opinions generally expressed by experts.

- Aquatic function: mastering water(s) and first the rain

- Funeral function: helping the “Passage” and next life

- Security function: self-protection / enemies frightened

- Cultural function: from sculptures read on drums and sounds emitted ceremonial function: from Royal courts to ethnic or family festivities Economic function: drums treasured up, and easy to mint

About bronze drum’s casting avatars

After rustic attempts probably emerged few bronze drums’ “centers” along the Red River basin if we consider the findings observed during our trips:

- It is attested that bronze drums were first casted with stone or ceramic molds before the invention of piece-mold casting techniques preceeding the final one-piece lost wax concept. Contrary to legends both ultimate wax techniques were used in parallel and not only successively, corresponding to different production costs or specific workers or available ores.

- Along the Red River basin piece-mold techniques were not the apanage of (northern) Yunnan nor lost wax the favourite of (southern) Tonkin as often written. Indeed, when looking carefully their mantles with magnifying glasses, very few were “one-piece made” not speaking of the addition of handles or in-relief animals.

- Bronze alloys were flexible, dependent of ores progressively diversified with the discovery of new “mixes” permitting better quality results or reducing the production costs. It cannot be stated that the rules were the same for any spot or any particular period through the history; meaning that all the classifications of origin based only on “alloy compositions” remain uncertain, all the more when are verified long distances transports for ingots or a possible “re-utilization” of bronze metal.

- Miniature drums were generally from 3 to 10 centimeters high with their tympan varying accordingly. They were massive pieces of metal not able to produce sounds, rarely capped with animals nor wearing distinct handles, poorly decorated (with exceptions), first casted with basic moulds permitting quick production and a cheap price but later, for the nicest, were used one-piece-lost-wax techniques. Their clientele was probably vast, from richest people buying them for gifts to other classes not capable economically to get bigger ones. They were used mainly for funeral purposes, one or several miniatures being often found near skeletons and sometimes around a big drum for the richest deceased.

In short, we are facing a large range of scenarios which do not help to clarify the situation until the discovery of adequate tools to date bronze. At least it demonstrates how the exchanges were numerous and creativity flourishing even if the more prestigious drums were not produced everywhere for at least two reasons: they needed diversified ores with top craftsmen to make them, and people able to help their promotion and distribution. As a consequence most of the old drums found came probably fully made from few spots never far from riverbeds or shores to facilitate the transport.

About bronze drums’ decoration

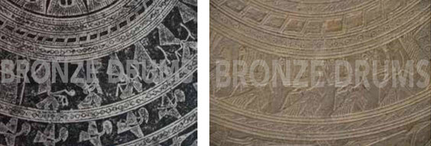

Once bronze drums existed, their makers seem to have taken advantage of the new material to introduce decorations that progressively covered both the tympanum and the mantle. Among clusters two kinds of decoration co-existed: geometric and figurative.

Apparently the adventure of the decorative frame began with a simple composition of geometric designs, issued from ceramics or painted woods, and progressively evolved with others more complex in provenance from local sceneries and soon exotic reminiscences from the northern steppes to tropical Java or Borneo.

Geometric decorations

Geometric decorations were the main designs on both tympanum and mantle.

Western scholars first defined the tympan central ornament as star or sun supposed to be part of a kind of cosmological system. It offered a nice way to introduce metaphysical values in accordance with a supposed animism.

Brilliant but never convincing theories were built about the number of star-points encountered, often from eight to sixteen. In this book, for the sake of consistency, it was also spoken of star or sun but such cosmic status was never demonstrated and other hypothesis can be proposed, based on facts summarized below:

- For metallurgists and musicians, it appears necessary to have a thicker surface at the drum’s centre where the mallet would strike, not only to avoid any damage but also to be heard very far. The format of a star (or sun) with its in-relief points very regularly separated looks optimum for a better “flying sound” without necessity of any other explanation.

- For artists, it is always difficult to find a way to “delimit a circumference” (the tympanum here) and particularly its centre for a better decoration around it. Geometric multi ray central designs could have been esthetically optimum without necessity of any other “cosmical” reasons.

- For local people, in most countries visited if you ask a peasant to draw a star, they will make a kind of circle but never a multi-rays design as westerners at first dreamed.

Not forgetting, at least for all Heger I types, the “inter-radial” designs between star- points, generally triangles or chevrons or slanting lines, or “peacock feathers”, giving possibly superior messages even if the concept of star or sun will probably survive in our minds. The reader is also free to imagine what represented the other geometrical designs never clearly justified even if, depending on the country, some local explanations were reported. We can only see that they were often composed of dashes or angles, added or not, to make nice balanced compositions to fill the gaps to decorate. “Easy for the hand and easy for the eye” as artists say, may be without necessity to find other cultural explanations for these geometric design often coming directly from neolithic ages; “illiterate customers” being probably more attracted by figurative decorations.

Figurative decorations

Figurative decorations were apparently loved by everyone, everywhere, if we consider their diversity and the great quality of their achievements on bronze drums. (Fig. 3 to 5) With flora or fauna a-plat or in-relief, like the famous frogs on the tympanum, or bands of flying birds of any specie, or elephants going down the mantle ornamented with flowers or grains; with also feathered humans playing a major role, being dancers or warriors or boat passengers or house-inhabitants. Alike on the walls of western cathedrals, the subliminal messages if any were certainly easier to signify when based on understandable scenes of life which could mean much more than their primary image: the festive feathered dances, at first a reality-show, could also be an homage to dead warriors or a prayer to the skies. Let us review and comment the main marks and hypotheses encountered:

- Feathered men after careful examination were probably not “bird men” but normal humans adorned with feather attributes. They were not performing “ornithomimic dances” as we know from various other cultures: the dancers and musicians depicted are ordinary men, perhaps in some cases women, with the feather attributes still used among southern Dayak in Indonesia for example.

- Houses (on Heger I) were from two types, often closed but with their inside inhabitants possibly seen “in transparence”. Either O house with an “eye-shape” decoration at the end of a convex roof (Hoang Ha drum example) or H house (Moulié drum for example) with its gable roof decorated with a circle topped by three plumes derived from a bird’s head as in the Toraja region in Sulawesi. Whatever daily life scenes or funeral rites they could recall, from southern tropical influences with large open platforms to northern housing more intimate habits.

- Houses occupants: Resting on stone poles, the transparent walls of the houses allowed rice-thrashers or musicians to be seen inside, with gongs or drums or dancers. Musicians often used well known “mouth-organ” or “hornbill” wind instruments also played on the walls of Angkor as nowadays in the mountains or islands: the old melodies remain unknown but their acoustics can be conjectured.

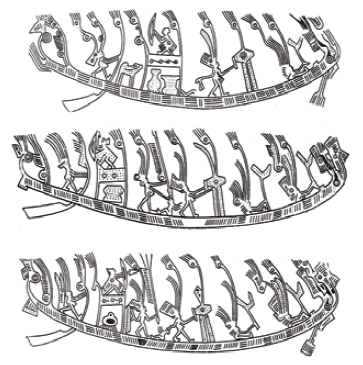

- Ships, with or without feathered men on board, varied from simple canoes to bigger boats, from provincial versions of river races to “sea born ships” with prows. Some of them contained drums, maybe used to spur on the rowers, maybe exported to any country, maybe featuring ships of the dead. None of the boats on Đông Sơn drums is identical to any other in all details but look strangely concise without any mast or sail.

- Birds numerous representations were particularly discussed to be seen or not with metaphysical connections even if their heads were never turned towards the “star/sun center” of the tympanum, seeming to fly passively, clockwise or not, around it. Better to underline that they were usually aquatic species (cranes, swans, herons, etc); occasionally the long feathers of the crest met the wings and flying birds could alternate with perching ones in any event.

- Frogs (or toads) rapidly played a first role in drums’ decoration, with aquatic birds or fishes or water leaves, demonstrating clearly a major climatological function. Batrachians often in action of coupling relied on fertility if not sexual pleasure giving another dimension to the roles possibly devoted to bronze drums like important human motors.

- Other animals were represented of which (non-exhaustively), tiger, deer, lizard, horse, snail, bovid, with other flying or sitting birds like pelican, peacock or poultry, etc.

All these realistic decorations could be linked to the customers’ habits, with riverboat formats for inside the continent or sea boats with prows for the shores, with horses or deers from the northern steppes or buffalos from southern rice-fields... at least it was the first type of explanation given by scholars such as Frantz Heger and Henri Parmentier at the beginning of the 20th century.

Well adaptable to any situation, decoration played certainly a great role in a world of illiterates but the similarities encountered on drums discovered from north to south attested to the homogeneous reactions from numerous nationalities. Consequently many researchers favored other explanations based on spiritual bases: for Victor Goloubew the presence of boats not only represented factual scenes but used to express the trip between terrestrial life and future worlds after death. Going further, rare researchers considered the possible existence of a kind of spiritual community for the entire zone, even the “Vatican’s” example was amazingly mentioned without serious basis.

Furthermore, authors like Madeleine Colani followed by any modern scholars emphasized a probable “bi-influence” in ceremonial decorations. The fact is that, during the first millenary BCE, invasions not only came from northern people with their own languages and traditions but sometimes from the south with other idioms and themes: for example feathered dancer designs could refer to life forces and habits identified in the south. In any case the abundance and variety of decorations permitted to tailor, if needed, three classical type of messages according to sociologists; for the owner itself and its nearby circle, for its counterparts friends or enemies away, for the skies eventually; to help to provide questions and answers in diverse key circumstances of life. Not excluding to distinguish male or female drums playing a distinct role in ceremonials before to be temporarily buried not only for their safety but may be also as a way to maintain or recover their vital strengths.

In the absence or writings or any other decisive proof nothing is sure and comments must remain limited. At least it is tempting to bet on open-minded drums’ customers, first attracted by realistic scenes but possibly seduced by far-away or common myths including “Deluge” remembrances, bronze drums’ owners supposed elites being probably both devotees and collectors.

About the origins of bronze drums’ decoration, between MSEA and ISEA

Archeology, pivot for findings, is not able to explain all the possible origins and meanings of the bronze drums’ sophisticated decoration as questioned many times along our surveys.

Linguistic and ethnographic sources must also be requested without entering in their details to try to understand the Red River valley early products, Đông Sơn and Dian included. At times, when precisely bronze drums were “invented” during the second half of the first millennium BCE, linguists detected important movements of southern population Dayak from Borneo (Austronesian family of language) to northern continental territories peopled of Mon-Khmer minorities up to the highlands (Austroasiatic family of language).

Traces of resulting Chamic and Daik and Katric are always present in Viet and Lao idioms. Musical instruments offer a specific example of such “cross-breedings” involving Dayak (Borneo) but also the continental highlands including Mois of Vietnam, Burma, Laos, up to Chinese provinces: so well represented on drums was the mouth-organ made of a central resonant gourd with attached bamboo to play, near-called khèn in Vietnam and keledi in Borneo.

These facts give more importance to Victor Goloubew and Madeleine Colani hypothesis in favour of south-north influences and not only north-south ones as first imagined.

About decoration trends: Ngọc Lũ and Sông Đà drums comparison

Among thousands of drums discovered relatively few were completely decorated with sceneries on both tympanum and mantle, usually the best ones. It was especially the case for the “Đông Sơn” (Heger I) letting see near-similar designs during several centuries between BCE and CE.

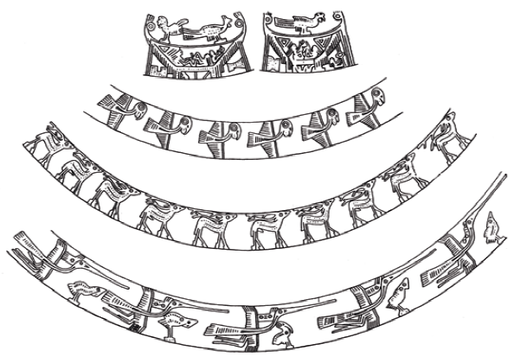

Therefore, for illiterate workers, strong oral traditions were crucial both for casting and decoration of drums, letting imagine places where apprentices could acquire or perfect their skills under the tutorship of recognized masters. A way permitting to conceive an homogeneous evolution of styles that ranged from simple “realism” in the beginning to more sophisticated “symbolism” later. Such persuasive trends were put in evidence by the recent works of Pierre Baptiste (Musée Guimet - Paris) commented too briefly below under the unique responsibility of the author of this book. Thus, comparing the sceneries recorded on the respective drums’ tympan of Ngọc Lũ and Sông Đà (Moulié - undoubtedly posterior) could be acknowledged an undeniable kinship but also any interesting developments. (Figs. 6 and 7)

The dancers and birds on the Ngọc Lũ (left) are very consistent with reality, almost “photographed”. Their counterparts (right) on the Sông Đà, although found in a similar location on the tympan, are more symbolically depicted with endless birds bodies and dancers almost disguised. (Fig. 6)

At left Ngọc Lũ gave the realist impression to be in a tropical village where they struck alternately rice or millet with two long poles. At right Sông Đà related the same story but with much more symbolically stylized people and houses. (Fig. 7)

Similar comparisons can be made between other masterpieces (for example for boats or musicians or houses sceneries) strongly suggesting a kind of “conservatory” of knowledge with perennial schools of drum-making instead of mere chance over centuries.

About bronze drum’s usages

Many early drums were discovered in cemeteries, sometimes complete with a lot of other gifts for rich people; for the middle class were found broken frog(s) or handle(s); poorest people being left out in any case. No doubt that drums were part of funeral ceremonies at least for prestige if not for other unknown rites, with, very rarely, bones or skull placed inside them.

They were certainly much more polyvalent as attested throughout history, by old Chinese texts to missionaries from the 18th century CE. By country many examples of their uses were cited: in case of wars to impress the enemies or to become trophies, as in China; at Court level when played in the presence of Royals, in Burma or Laos and as it is still the case in Cambodia or Thailand nowadays; to enjoy any private or public ceremony often in accordance with agricultural calendar (everywhere); to be loving gifts or even dowry (Laos; Indonesia); to please good or reject bad Spirits; not omitting the increasing number of present festivals in China or abroad: Yi, Zhuang, Dai, Miao or Mường etc.

All bronze drums were asked to influence the rain in case of droughts or floods: their huge and profound sounds with the help of their in-relief frogs and other aquatic designs, fishes or leaves, were supposed to reach the spirits to prevent or stop such disasters. Acoustically one drum could give the rhythm and many produce melodies based on imposed Chinese pentatonic rules.

Men at times gays, and often women supposed to have specific aptitudes, “shaman” or “medium” intermediaries, were chosen to play them. Diverse techniques were used as described separately depending not only on local habits and environments but also of drums’ respective dimensions, so different for a big Heger II than for a small Moko. The freedom to produce “hot sounds” by striking hard the tympanum (in case of war for example) or to emit “cold sounds” beating it slowly (in case of funeral for example) existed. On the “Moulié” (Sông Đà) two drums are depicted, and four on the “Vienna”, maybe only for transportation as it appeared in several other cases but why not for upper goals as said before?

In brief, due to that large spectre of uses and users, it can be confirmed how Bronze drums were important in day-to-day life in the entire area before to become wonderful pieces of collection. (see contemporary small panorama in final Appendice b).

About bronze drum’s trading

This important point has often been too neglected by historians or ethnologists may be more interested by the (supposed) metaphysical needs of humans and less by their permanent day-to day quest to get wealth and power, in brief by their basic material instincts not so far from ours. We cannot imagine such a successful long odyssey without particular efforts and organization to attract the customers at the scale of a sub-continent.

Other attested trades existed before, for jewels, for pearls, for textiles, with efficient relays along the main ways, harbours or early hubs. These intermediaries were first informed of the new products able to tempt their “customers”, maybe discussing the prices or the best arrangements for their region. In brief they were part of a primitive marketing approach influencing the production at origin and promoting an “elitist image” if needed. Along the way several places have been encountered, for example Ongbah Caves in Thailandor or Vilabouly in Laos, where bronze drums were probably concentrated (if not produced) before being distributed over large distances, maybe with specific well-guarded boats or caravans adapted to their transport, meaning embryonic “entrepreneurial” circuits.

Certainly, the different local and central governments had also to give their authorization, asking for taxes, promoting or not the operations. And firstly the Han Empire and its Chinese successors who governed around the gulf of Tonkin/Bac Bo till the 10th century CE, from where the main drum’s fluxes originated.

Not forgetting of course the essential role of the devotees, by definition basic customers personally or collectively involved, mostly animists but may be influenced locally by other civil or religious organizations more or less financially “involved” (or “opposed”) in both continental and maritime trails. The trilogy (producers/powers/customers) deserve to be more studied but, in any case, drums were important economically as money of exchange and part of the boarding up of treasure processes.

About bronze drums’ classification

Heger’s classification remains a reference but its successive numbers - from I to IV - must be revisited if we wish to consider their true chronological succession. Since their creation in 1902 by Frantz Heger the corresponding families are now better known:

- Heger I covered the early “mushroom-like type” of which the most famous until now were made under the umbrella of Đông Sơn, (in nowadays Vietnam) but existed also at north (in nowadays Chinese Yunnan).

- Heger II type was posteriorly produced in the mountains between Tonkin (possibly by Mường) and above all in Guangxi (China) and around. Generally larger and first more rustic than Heger I, they were long under-estimated but now look much more numerous, diversified and recurrent.

- Heger IV minority now cover either the earliest BCE ones called Wanjiaba by the Chinese or the last CE ones almost think decadent by the Vietnamese. Even if our exams were more propitious to the Chinese approach, both hypotheses are permitted as far as in any Culture the decadent models often resembled the primitive ones. Better to wait more exact dating techniques before to give final answer(s); privileging for now a common origin and decline along the Red River basin.

- Heger III were born few centuries after in Burma and must not be confused with the first families as it was since long the case; even if the old ones had normally an influence, a direct filiation remain to be proved between Heger II and Heger III. Amazingly, because erroneously, Heger III were presented to Emperor Napoléon III as the earliest original bronze drums from Vietnam and Siam respectively.

- Pejeng and Moko drums in Indonesia corresponded to another “hour-glass” family type not studied by Frantz Heger. Both were first made of bronze with a lot of similarities even if Moko looked rougher and much smaller than Pejeng. So different from Dongsonian drum, albeit historically inspired by them, they corresponded to a totally different culture always unknown, Moko(s) unique survivors of the family being now made of brass.

- Why not to create a supplementary new class H 5 for Pejeng and Moko, also a way to express a posthumous homage to Frantz Heger?

Conclusion or very last Thoughts

Following the bronze drums movements throughout Southeast Asia, their area of production and distribution may be conceptualized as a large archaeological site containing different clusters, at a time when present States and frontiers were not yet formed.

Journeying in space and time to consider bronze drums with the help of Heger classification, albeit imperfect and incomplete, did permit to locate nearly three thousand pieces, more than half of them in South China, not forgetting the smuggled ones and the continual findings all over the area.

Enduring more than two and a half millenaries for recurrent millions of people covering Southeast Asian area, drums were much more than a curiosity or a “detail of history” as sometimes considered: for sure it existed a vigorous and tenacious Bronze Drum Culture.

To borrow from a seismic vocabulary for the drums’ Odyssey it first existed a kind of “big eruption” around the Red River Valley and then Guangxi near Bac Bo (Tonkin gulf) at the verge of BCE/CE. Looking like fireworks for a finishing Bronze Age meeting an Animist World not yet “spoiled” by imported great religions, it was a kind of last encounter between two Universes condemned to decline but flourishing together. This was followed, after a time lapse of nearly one thousand years, by two major “replicas” in Burma and Indonesia respectively.

Cross-crossing territories, the early peoples involved could be very diverse, coming from the north or from the south, speaking distinct languages, divided into small kingdoms or clans with specific myths. But all had much in common being at the same first sedentary stage of human evolution with probably, on a day-to-day basis, a strong desire to take advantage of any new metallurgic techniques to support their lives and respective beliefs. By taking a bird’s eye view over the entire area it can be imagined how new bronze drums, cultural and peaceful products, notwithstanding local wars or colonial trends, were received with appeal and possibly enthusiasm by all. Beyond their thundering musical qualities sculpted drums permitted the visualization of realistic or mythical scenes and outshined their predecessors made of wood and skins. Their beauty added to their high price, could explain their success, both elitist and popular by imitation, without necessity to refer to any hypothetical “cultural super power”.

Compared with the Asian population in total the people involved remained a minority but they covered huge terrestrial and maritime territories. Even illiterate, they demonstrated with bronze drums their basic aptitudes to commerce and to upgrade their cultural tools - two main “motors of dynamism” along the ages.

Situations changed drastically in seven decades after the end of WW2

Formerly, before the Maoist revolution in China and the end of colonial times in Indochina and Archipelagos, bronze drums remained popular in many ethnicities, mainly to fulfill agricultural purposes or to be part of family rites from births to funerals. It was particularly the case in remote mountainous areas with ceremonies involving one or many bronze drums played by dedicated musician(s), in southern China as in many countries of Indochina-not omitting Moko’s owners in Indonesian Alor island(s).

Even if elites everywhere had become more collectors than devotees. Revolutionary modern times put an end, with only rare exceptions, to twenty-five centuries of more or less intense usage along the ages, at times forgotten...

Nowadays, based on our trips over two years, it appears that bronze drums practices did regressed so much to become rare and no more crucial for peoples. Only a few domestic sequences were encountered where a candle was lit on a drum’s tympan or animal blood poured-on to ask for any health or to solve sentimental affairs. Droughts or flooding initiating “drums’ prayers” were only reported sporadically by old farmers.

The majority of surviving ceremonies seem to less correspond to believers’ necessities than to reminiscences of bronze drums’ habits, if not pure nostalgia or folklore. Of which the seasonal festivals of “Nationalities” in China or, in Myanmar, the Kayah ceremonies in churches with seasonal dances and drums’ orchestra in remote villages; or, in Alor “give and take” Moko practices...of course not speaking of increasing tourists’ demands.

Can we expect any “bronze drum resurrection case”? Surely not but maybe ASEAN experts could definitely help to better know a such beautiful culture well received by all its countries members being often at loggerheads on other subjects.

Between ups and downs, forgotten findings and modern imitations, present times offer a good opportunity to better appreciate and rehabilitate Bronze Drums. Not only and first in south-east Asia but also at a world level considering their unique originality and the great number of collectors of masterpieces already displayed in the best museums around the Planet, being undoubtedly part of Humanity’s Treasures.

May the readers be involved in such challenges!