Southern Archipelagos

Indonesia-Malaysia-Singapore

Looking at a map of the archipelagos concerned in the south of eastern Asia, the first impression is its immensity, from Malaysia to Indonesia and neighboring islands.

A kind of huge trapezoidal form spanning thousands of kilometers, most of which is covered by water. A very minor share is devoted to a few ranges of islands, sometimes as big as Borneo

(measuring 1.5 times the size of France) and sometimes appearing as near- invisible seeds on the waters.

Fourteen thousands years ago, at the end of the last glaciation, before the rise of the sea-levels of about one hundred and twenty meters, most of these islands were part of the south-Asian

mainland, meaning that a great number of archipelagos inhabitants had common roots and probably always maintained recurrent commercial and cultural routes using rowing or sailing boats in

accordance with the monsoons’ winds.

In such a case, distances and waters not account for too much and allowed any societal improvements to be shared between mainland and islands, with some delays of course as it was the case for

the metallic ages in general and particularly for the bronze coming from the north.

Today, looking at the specific discoveries in the archipelagos, two periods may be distinguished with different families of bronze drums:

- The first one consisted of terrestrial or maritime drum’s importations from the northern Red River Valley and Guangxi zones, around the turn of the first millennium BCE/CE. Optically a “mushroom shaped family”of which about sixty pieces (mainly Heger I) had been found in the archipelagos.

- The second period during probably the first millenary ce corresponded to the creation of a local “hour-glass shape” family of bronze drums named “Pejeng” limited to the Indonesian area and now extinct. In parallel, if not successively, with a branch named “Moko” always produced in Java, uniquely for far away islet(s) named Alor.

Even after local visits, reading or meeting the best specialists from A.J. Bernet Kempers to Pierre-Yves Manguin (EFEO) and Ambra Calo, the following commentaries must be considered as hypotheses, many more future discoveries being probable in such huge but up to now little-known area.

The Red River Valley and Guangxi drums’ importations in Archipelagos

The typical Heger I decoration as already noted is characterized, from among others, by adornments of birds and/or feathered humans and/or boats motifs which could be compared to local ceremonial

and religious environments for elites (mana) in the Polynesian or (semangat) in the Malay worlds. As it was first pointed out by (EFEO) Madeleine Colani and Victor Goloubew (around 1930)

historical links between Red River mainland and Borneo (Kayak) or other islands existed for long. As a result of early movements of populations, west/east, north/south, and vice versa, bronze

designs were probably influenced by both cultural sides, continental and oceanic. Be that as it may, the drums were apparently welcomed as part of an ancestral heritage by southern Archipelagos,

and quickly became put in the tombs. Therefore these drums were apparently never produced locally at the difference of basic bronze articles, for example axes or arrows, melted from metallic

ingots coming from abroad. Drums probably came ready-made from the northern Red River valley or Guangxi, as “deluxe” items which had to be transported with care, meaning at high cost for their

customers, between MSEA (Mainland) and ISEA (Island South East Asia). The Mainland routes, taking at least three months, has been already described in corresponding chapters, covering the main

waterways including successively the Mekong basin (via present Laos and Thailand central plateau) down to the Chao Praya and other southern Thai rivers, and then the Malaysian waters before

western Indonesia.

The Maritime routes, taking less than one month when winds permitted a “sea- connection” from Tonkin/Bac Bao gulf to southern islands was another way to import, supported by the relatively great

number of drums found in the eastern part of Java or other islands. Probably via the main harbors known to have been centres of great direct currents of trades, ceramics, metals, jewelry,

mirrors, over the centuries.

Foreign objects concentrations, including not only bronze drums in central Java or south Sumatra, demonstrated the connections early established between chiefdoms so far away. Were the maritime

drums’ routes largely subsequent to the mainland routes as brightly suggested by Mrs Ambra Calo? Probably, pending exact bronze dating techniques and also the fact that, once they reached the

islands, the drums entered a series of extended intra or inter-island trade networks; complicating a diagnosis about their point of entry.

Bronze drums remain highly respected up to the present day, if not worshipped at times individually by Hindus and Moslems. Generally the discovered specimen came from digging works, public if a

road or private if a house was concerned, not permitting their conservation in situ but in museums.

To facilitate possible trips or researches our presentation will be based on the main museums where most of the imported antique bronze drums can be seen today. In total, nearly forty old pieces,

chiefly “mushroom typed”, were discovered in Java, mainly in eastern territories, ten or so in the south of Sumatra as in present-day continental Malaysia, and less in the other islands including

Borneo, poor results certainly due to the rare research up to now. Astonishingly no one was found in Bali so famous for its Pejeng production to come.

As they were all produced far away, these drums’ descriptions will not be too detailed again after previous chapters China and Vietnam. All their designs, geometrical or not, are classical and

their local success apparently meant that they were as much understood or at least welcomed as in the northern countries, may be with a better acceptance for the feathered dancers or the sailing

boats in such equatorial and maritime environments.

Traces are missing about their local uses and importance at that time, with the exception of a few carved monoliths showing the transport of a drum. (Fig. 1)

Only their presence in tombs told us that they were part of the basic human beliefs and not simply fashionable pieces for rich owner’s collection.

Consequently their presentation for southern Archipelagos will be more a kind of brief catalogue based on a necessary selection. Things will be different at the end of this chapter when looking

at the local bronze drums “hour glass” productions, so-said Pejeng and Moko types.

Indonesian Museums

The two museums of Jakarta (National), and Surabaya (Negeri Mpu Tantular), contain the main early drum discoveries kept in Indonesia from the islands of Sumatra, Java, Borneo, and Nusa Tengarra Province; their Pejeng and Moko collections will be further related.

Djakarta National Museum (DNM)

Two rooms are devoted to early imported bronze drums, one in the old building containing the first findings, another in the contiguous new aisle. Usefully it is pointed out that, at least in the

old times, no copper or iron or lead ores were discovered in Indonesia, meaning also no great expertise in metallurgy, the name of “Paleometallic” age covering these displays.

Of the four drums in the oldest room, ornamented with 4x1 toads on the tympanum and four handles, the Serpong Banten (west Java) stands out for its beauty and large fan of designs (first and biggest one on Fig. 3). It shows a true synthesis of the “cosmology” supposed to be figured on Heger I bronze drums (Figs. 4-5), in brief:

- on the tympanum, around its central star (12 rays), are concentric designs with, in rotation, flying birds and geometric symbols for earth (grains) and aquatic worlds, surrounded by one magnificent toad on the border of each quarter

- on the upper part of the bulb are bands of well stylized sailing boats

- on the middle part of the bulb are flying birds and feathered dancers or warriors

- on its lower part are well-sculpted “a plat” horses and elephants (of about L15 cm).

From the three Heger I drums in the new aisle of the Museum (Fig. 2), the two biggest with 4x1 frogs came from West Tengara and Sangeang Island and a smaller (D60/H40 cm) without frogs was found in Kur island (Maluku Province), imported probably from Guangxi as far as it displays very exceptionally Chinese letters cast with the drum (and not later) during the Easter Han period at the beginning of CE.

The huge one (D120 / H100 cm) was partly broken with a large hole on the bulb (Fig. 6) as was the medium one (D100 / H70 cm) but their sculptures, when not rubbed out in some places, are nicely done with their central star and added in-relief frogs or their “a-plat” elephants on the bulb. Not speaking of the classical designs already mentioned for the old aisle specimen.

Surabaya Neger Mpu Tantular Museum (S. M.)

Built at about twenty kilometers from the town centre where until recently the old one was located this new museum is not as rich, in terms of bronze drum’s, as the Djakarta National, but a visit

is valuable. Even if several notices are bizarre, doubling the age of the Đông Sơn’s culture for example.

Near a half-dozen “mushroom type” drums are on display and may be the most interesting was discovered by chance in 1981 in Kradenanrejo (Lamongan district - East Java). It was part of a child

burial container made of two assembled bronze drums: on the top was a Heger I (D49/H42 cm) covering a Pejeng type bronze drum, the double drum containing the teeth and bones of a child with

ornaments and pottery. (Figs. 7-8)

Although partly broken and corroded, this duo carries of course a lot of emotional values and demonstrates a kind of affiliation between Heger I and Pejeng. Another classical bronze drum with

child bones (secondary) burial was also found in Plawangan (central Java).

From Batu Buruk (Terrangan) is displayed a great tympanum (D100 cm) and also two big drums, typically Heger I, with respective dimensions (D100 / H90 cm) and (D90 / H70 cm). The biggest, from Geslik (Nekkara prov.) without frogs, suffered a lot (ankles broken and tympan corroded). Meanwhile, its remaining original designs and Đông Sơn’s classical facture are typical of the discoveries made in Java.

The last one found in Tuban (east Java) without tympanum is interesting because it was upturned and contained a bronze figurine of an elephant (H32 cm), and also a bronze axe possibly cast in Java with imported ingots in absence of local copper ores. (Fig. 9)

Malaysian Museums

Our main concern are the Kuala Lumpur Negara and the Singapore Asian Civilisation Museums. Sumatra and the Malay peninsula, a long time before the creation of the Singapore modern State, were the

natural “bridges” between northern mainland (MSEA) and southern islands (ISEA). One route followed the course of the Mennan Pattani River, from Songhkla province (south Thailand) to the Malaysian

sea near Salangor, another route followed the Kelantan River valley with nearby tin and gold ores explaining the local wealth.

Bronze drums’ trades are nicely attested by a few sculptures on huge monoliths showing an early tradition of bronze drums’ transportation in many local areas; for example in Airpurah Pasemah

plateau (south Sumatra) where a drum sculpted on a rock is held by two human figures and under the drum is the head of a dog between other animal (totemic) faces including a crocodile. (Fig. 1)

Kuala Lumpur Negara National Museum

The discovery of a pair of drums at Kampong Sungai Lang (Selangor) had since been classified as a symbolic burial for a personage of a high social status in his community. The excavation revealed

that the drums were buried face down on a sandal hardwood plank of two meters long believed to have been taken from an old boat. They were enclosed in earth piled up as a mound measuring about 5

m. at ground level and 1 m. at its peak.

A circular array of pots surrounded the drums; under one pot numerous red glass beads were also found and radio carbon techniques for the wooden planks suggest a late century BCE dating. The

largest drum has four three-dimensional toad motifs (4x1 - one lost) and two dimensional bird motifs on its beautiful remaining tympanum (D45 cm) with a twelve rays central star. (Fig. 10)

Road improvements in 1964 at Batu Buruk (peninsula) led to the discovery of a pair of Red River Valley drums (D45 and 36 cm) buried upside/down and soon reduced to fragments by bulldozers.

Apparently, in their inverted position, they were used as containers with an iron spearhead attached (with rust), weave traces, glass beads, pottery. (Fig. 11)

A bronze bell (H50 cm) was found in the vicinity, and in the region many others with the same casting and designs, meaning that they came also from the north as products of the same sophisticated

bronze family at large. Once again we can imagine, as in Thailand (Ongbah) or elsewhere the early existence of warehouses for expensive cultural materials imported in harbors or transit points of

the Malay Peninsula.

Singapore Asian Civilisation Museum - SACM

The museum is situated in the Old ex-Governor Palace. The most interesting bronze drums of this Museum having rich projects of acquisitions are based on Indonesian productions, Pejeng and Moko

“hour-glass shaped” paving the way for the second part of this chapter.

Previously, the presence of two old “pots” cleverly presented side by side in the same showcase must be mentioned. Probably contemporaneous, their dimensions are comparable but one is only a

container with a cover and the other a Heger I “mushroom typed” bronze drum (D55/H45 cm) without frogs on the top but aquatic designs everywhere with boats and feathered people and animals. Their

precise findings are unknown and their very classical styles have already been described but they are, for sure, members of the same ceremonial family so many times already attested. (Fig. 12)

The Pejeng-style huge bronze drum in the Singapore ACM

If you loved the famous Jules Verne’s book “From the Earth to the Moon” (ed. 1865) you will admire the way a huge stylised model of the Pejeng drum is presented by the Museum, like a kind of

rocket ready to explore the mysterious Universe—maybe a remake of any “cosmical” ambition of antique drums (Figs. 13-14)

Said to come from Lumagiang - east Java (via a dealer from Europe?) this huge Pejeng type drum (D81/H161 cm), the second largest known after the Moon of Pejeng in Bali, had been too restored if

not rebuilt but it permits at least a clear reading of the sculpted details on bulb and tympanum, not so visible on many other specimens described in the coming pages. All were obligatorily cast

in many pieces to permit such huge formats, probably from the middle of the first millenary CE.

The “Moko” bronze drums in the Singapore ACM

The oldest are in bronze and the modern ones in brass (copper and zinc) from the 20th century, a cheaper metallic alloy easy to work with (in average H50 cm as in Fig. 15). Some are classified “mini Pejeng” (smallest: D2/H8 cm), instead of Moko.

The Indonesian hourglass-shaped bronze drum's Pejeng

Introduction

Pejeng name as first reported in 1705 by Dutch Officer Rumphius is derived from the village where the biggest bronze drum, venerated as the “Moon of Pejeng”, remains. A Hindu-Balinese legend spoke of a fallen wheel-axle of the moon’s carriage in the night sky. (Figs. 19-20-21)

Nowadays, only twenty-one archaeological Pejeng drums are known from Java (15) and Bali (6) and possibly five to be confirmed in remote islands—probably many more will be discovered in the future.

Typologies compared

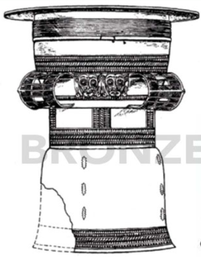

As already seen in the Singapore SCM (Fig. 13-14) “Hour-glass-shaped” type mean symmetrical upper and lower parts of the base separated by a mid-section as a waist-a stylized elongation compared

with the shorter mushroom-type type from the mainland. A new shape probably looking more like traditional drums made of wood, long enough to be played and easily transported by a team, well

adapted to equatorial outdoors habits, with a powerful sonority. (Fig. 16)

On the upper Pejeng mantle are four pairs of face motifs with bulging eyes and long earlobes with various earrings. Similar so-called primitive but very expressive motifs were carved on

contemporary sarcophagi in stone (volcanic tuff) found in many Balinese sites with comparable carved human figures, containing bones and precious artefacts. (Fig. 17)

Pejeng tympan generally bore spiral motifs with possibly knobs around a protruding central star (or sun) if not petals of a tropical flower. Designs are repeated over the four quadrants, sizing

the round shape of the rim extending as a lip over the upper section of the mantle. At least two pairs of perforated big handles connected the upper and the mid sections of the drum ornamented

with concentric bands, sometimes with geometric saw- tooth or combs and heads motifs, a local stylisation also found on axes or other bronze typical artefacts from Timor to Sulawesi.

No doubt: from concepts and processes coming far away from the northern continent, the Indonesians were able to make drastic style and technique innovations in accordance with their existing

cultures. From Heger types with a tympanum much larger than the height, the proportion became clearly inversed and the ways to use the new huge drums, individually or collectively, ought to

differ grandly.

Far indeed from the sophisticated designs of the Red River valley, without anymore boat or bird motifs, these new drums represented a very interesting adaptation to the local culture.

Long delays were probably necessary so that mutations could take place, first to understand and learn the Heger imported pieces, then to shape new formats, and finally to get the ores, and train

adequate workers. Maybe Pejeng drums did not appear before the second part of the first millenary ce, not forgetting probable foreign influences. For example, parts of a Pejeng mould were found

in Sembiran (north-east of Bali) old important port for trades with India Southeastern Arikamedu (in contact with the Roman Empire) from where Hindu feminine myths and rites based on water and

rice possibly originated.

Apparently so different, both Đông Sơn and Pejeng drums followed a precise decorative schema of motifs and continued to share some features, like the geometric decoration of the concentric bands.

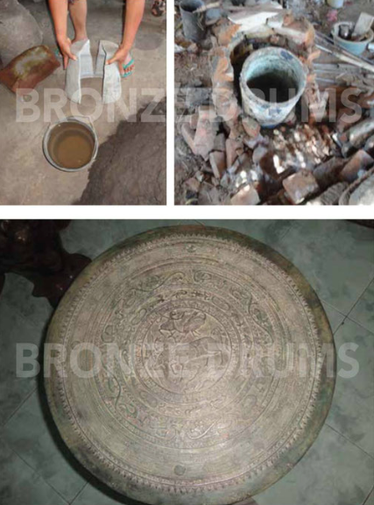

Casting and moulds

In the village of Manuaba (central Bali) stone moulds carved with the typical decoration of Pejeng drums were found, now revered in the local Hindu temple (Pura Pusen – Desa - Masceti) (Fig. 18).

From their examination, it can be deduced that an adapted methodology using stone was practised; several sections were joined by inserting the tympanum with rim to the other mantle’s parts;

handles and other major “in relief” decorations being casted separately and then added. The alloy, from imported ingots or recuperation processes in absence of local ores, was strongly based on

copper, with low tin, for a very thick result.

Depending on further analysis, the stone moulds were carved in the “reverse” shape to imprint wax or clay; the molten metal was poured and the remaining clay broken after solidification. At least

we can admire the great quality of the Manuaba stone mould’s sculptures, probably made for the upper section of a mantle.

The Moon of Pejeng

Gianyar (central Bali), a location associated with the earliest Balinese Royal power (10th century ce), is also a place where tablets of Mahayana (Tantric) Buddhism from 8th ce were found in the

Pakerisan River valley.

There, long time unearthed and found by chance the so-called Moon of Pejeng is kept in Pura Penataran Sasih. It was the state temple of the Royal dynasty and the huge bronze drum, despite its

dimensions and weight, was put on the top of a small dedicated temple inside the great sacred enclosure. (Fig. 19)

You must know to pay attention under the roof to the large tympanum (D160 cm) facing the coming visitor who can only get a lateral and partial and bad view of the cylinder 198 centimetres long of

the partly hidden drum, three meters above the ground.

To understand the huge chef-d’œuvre, better to refer to its schema from A.J. Bernett Kampers (Fig. 21) before to consider its parts on exceptional photos. (Fig. 20)

The stylistic similarities of the Pejeng drums with traditional three-piece rice steamers and the local representations of the Goddess of rice (Dewi Sri)... were often pointed out to explain the

Pejeng format. They underline the importance of the links between Bronze Age and rice verified from North to South Asia and also in accordance with the pre-Hindu animistic beliefs throughout the

Malay world.

More researches are requested but, meanwhile, the numerous devotees of all origins and religions converge to the huge bronze Moon to pray or at least respectfully salute.

Pejeng drums and funerals including human remains

From Kradedanrejo (east Java), now in the Surabaya Mpu Tantular museum, the double- drum child burial site was already mentioned (Fig. 8). In 1997 two Pejeng drums with human remains, one

containing an adult in foetal position with jewels and other funeral gifts, were found in Manikliyu/Bali.

In 2009, a miniature Pejeng bronze drum was found placed by the skull of an adult buried inside a stone sarcophagus in association with conical golden plaques, beads and ornaments at the burial

site of Pangkung Paruk (north Bali).

Another specimen (H27/D16cm) was found in the same district (Uluran) with burial goods also—without more precise ideas about the funeral rites involved. Comparable to big sizes made for public

temples and ceremonies these drums could be discovered in larger quantities in the future, possibly made to be buried with humans.

The Indonesian hourglass-shaped bronze drum's Moko

The Moko name was first mentioned (1851) by D.W.C. Baron van Lijnden, the Dutch Resident of Timor, as a kind of “drum or cymbal, shaped like a spittoon with a cover, called locally Moko”. (Fig.

15)

Both Pejeng and Moko are evidently part of a same family but with so different characteristics, formats, decorations, ways of casting, if not age, that their first description necessitates two

respective paragraphs.

Moko drums’ family, by comparison with Pejeng

Now only preserved in Alor islands even if made in Java the Moko(s) basic type looks, at first glance, like the Pejeng family. On old ones, in bronze, were similar decorative elements; on new

ones, made in brass, all kind of additional decorations were imagined to please the customers and marketing catalogues are flourishing. (Fig. 22)

Moko tympan(s) are normally flat or slightly convex. They can be undecorated, or with a simple flower (sometimes trademark of the maker), or with stars, or concentric circles cut into the surface

and possibly in relief.

Moko handles usually number two or four, exceptionally eight, on the upper part of the mantles. Cast separately the rustic handles may be compact or perforated, spaced equidistantly around the

mantle, another distinct difference with Heger and Pejeng. (Fig. 15)

Only modern cement moulds of moko(s) were up to now found in Java and never in Bali, corresponding to Pejeng stone ones. A horizontal welding line, marking the joining of two separately cast

sections for Moko(s) is said to be a key difference between types along the ages. Actually three Moko sections are cast in Java, one for the tympanum, two for the mantle, handles apart. (see

Annex below)

Pejeng(s) and Moko(s), a ‘hen or eggs’ story?

There is no complete evidence why old Moko(s), made of bronze and probably with stone moulds also, should not date as far back as Pejeng.

Did Moko derives from Pejeng?

It is the position adopted by the great majority of researchers, invoking in addition their basic “vulgar” utilisation for bridal dowry or a form of currency, such as in East Timor where

mini-specimens in gold or silver were reported at high prices during the last century.

The recent multiplication of brass-items (sold for under 50 USD each for the small) added to “devalue” Moko(s) and the ways they were considered and aged.

Or could it be the contrary?

At least, can be mentioned again A.J. Bernet Kempers, highly respected specialist who did not exclude in 1988 to “call the Pejeng drum a gigantic Moko” (meaning a possible anteriority of the last

one).

Meanwhile Mrs Ambra Calo cleverly noted in 2014: “the lack of evidence for the early production of Moko during the late first millennium ce... all other hypothesis remaining speculative... such

drums having never be excavated in archaeological contexts”.

A Few Parting Thoughts

Bronze drums with possibly a minimum of bronze casting technology were transported from MSEA to ISEA, leading to further local productions of Pejeng and Moko new types.

Directly, via the sea, or transiting via the continental territories, Red River Valley or Guangxi early drums (generally Heger I type and only four Heger IV) were received not only as prestigious

gifts by the rich elite but became part of strong religious beliefs as attested in many tombs. Inversely, Archipelagos had probably influenced the continental drums’ designs from the beginning,

for example with their feathered men or tropical styles.

The later invention of a local new “hour-glass-shaped” type, long after the imported “mushroom-shaped”, was a revolution to be credited to the ISEA world. A kind of performance not seen elsewhere

historically, even in Burma where the Heger III types were not so distinct from the old models inherited from China and/or Vietnam.

Pejeng casting was interrupted long ago for unknown reasons but Moko(s) continued to be produced by thousands until now. Meanwhile, both types are important, the rare old Pejeng drums being

venerated and the innumerable Moko ones remaining a crucial part of the present social life in Alor island(s) and a commercial success-story abroad.

All reasons in favor of considering the southern Archipelagos area as the fourth and last Cluster (no. 4) in our Bronze drums story; coming after clusters no. 1 for Red River Valley, no. 2 for

Guangxi, and no. 3 for Kayah/Myanmar.

The up and coming religions, Hinduism, Buddhism and then Islamism or Christianism helped to “kill” the Pejeng production but from an unknown culture which created this new type of drums, probably

more numerous than thought from the rare discoveries made up to now. With the help of the best Universities, the southern Archipelagos has to be studied carefully, a lot of territories much be

involved from Borneo to Sulawesi and other islands, not forgetting nearby Philippines.

This will probably come up with surprises giving more emphasis to the ISEA drums area, in connection or not with MSEA.

Annex to Trips in search of Moko drums in Indonesia

Moko (Producers) in Mojokerto (East Java)

Only one hour by car from Surabaya, Mojokerto is an historical centre of metallurgic activities from gold to brass. All artefacts can be made, from pots to statues, with a kind of monopole for

Moko drums.

To cast them, after visiting three small workshops with few workers and archaic tools, the same rustic methodology was proudly passed down through generations. From old techniques modern changes

concerned the alloy, bronze (copper/tin) being replaced by brass (copper/zinc) less costly albeit less beautiful, and also moulds now in cement to impress the decoration into the wax instead of

stone for Pejeng and probably early Moko.

In brief, the sequence to obtain a Moko takes about four weeks, of which, for the mantle:

- two inner clay cores are molded

- mantle decorations (face motifs included) are printed on wax put inside (bivalve) cement moulds (pre-carved or using pre-formated plastic instead of wax)

- hot alloy is poured over the moulds, using adequate holes (heating from open earth oven to brick melting furnace)

- moulds are removed when metal cools off; sections and handles are welded

- final adjustments are made with a small hammer and glue if needed.

For the tympanum decorated or not, a circular wax model is created to cast it separately according to the same phases, another innovation versus the old Moko and Pejeng drums when the tympanum was possibly cast together with the upper section of the mantle.

Handles can be more than usually four (up to eight) and are spaced equidistantly around the mantle, cast separately, solid or perforated.

Historically the local customers were from Alor Island(s), with only few classical models produced, packed, and sent by sea from Java. (see Fig. 22)

Nowadays, producers are also making Moko “curiosities” according to requests from tourists or abroad, for example with any blazon replacing the faces... and to do so, German imported costly ores

are considered the purest. (Fig. 23)

Question mark: Were Pejeng drums also cast, as well as in Bali, in the metallurgic area documented for long and including Mojokerto, Tuban and Gresik, now hosting large copper industrial plants?

Pending the possible discovery of Pejeng moulds in that region.

Moko (customers) in Alor, Moko drums’ conservatory

Alor is a small but beautiful archipelago composed of eighteen inhabited islands (plus many small others) at the eastern end of the Indonesian territories, near Oriental Timor and other Papuan

sites. They were frontiers between Portuguese and Dutch colonial possessions a long time ago, before Indonesia Independence giving birth to the present East Nusa Tengarra Province. Not so far

away from Australia, 1300 km from Bali.

Cora, Alice Du Bois (1903-1991), from Harvard University, was among the first scholars to stay largely there just before WW2, publishing anthropologist studies. She mentioned how people, mostly

Papuan and without central government, lived in small villages where women hunted, fished and worked in the fields while men were taking care of finances and metallic drums (about 20,000 recensed

at that time), objects of profitable transactions. From Jakarta it took Cora Du Bois one week of navigation to reach the place nowadays accessible in four hours by plane via the small hub of

Kupang, with the last thirty minutes on board a daily turboprop to the Alor main island, capital Kalabahi.

There was created in 2003 a small museum named “1000 Moko” which host today about fifty specimens of drums among other local remains while a small village has been restored in Takpala (20 kms

away) with wooden thatched chalets housing Moko under their roofs. Generally Alorese people are very open to “discuss Moko”, most women of any cult (from Muslims - the majority - to Christians,

mainly Protestants) having received as marriage presents drums made far away in Java; even if the importance given to them can vary greatly from simple folklore to revered ancestral values, in

absence of any written archives.

“If they don’t get Moko, brides receive an equivalent amount of money”, which varies greatly between $50 for the basic new models in brass to $4000 for antique bronze ones - depending on social

class. It is said that money is preferred by the younger generation...

Inside the “1000 Moko Museum” in Kalabahi”

The first place has been given to the unique old Heger I type found by chance in the northwest of Alor in 1972 at Kabupaten. Huge “mushroom-typed piece” (D92/H68 cm) with twelve rays central star the drum was unearthed by a peasant, having much suffered from its long burial (Fig. 26). One of the four big toads on the top is missing and the circular decorations around the tympan and the superior part of the mantle were nearly rubbed out but it closely resembles other pieces from North Vietnam’s Hai Chun province, made two millennia ago. In Alor it is revered as a direct ancestor and named Nekara Moko supposed to be part of the great family of Moko, appellation meaning locally metal-drum with a given name added.

By contrast all the other “hour-glass type” drums of the Museum look younger than Nekara, from the cleanest and lightest ones in brass correctly described as “very new” to the heaviest others in

bronze described by contrast “very old”. All have four handles but some of them are completely undecorated, the cheapest, while the others bear the “classical” Moko sculptures. The latter are

mainly composed of facial images of antique local if not Indian fertility Goddess—often with plants or animals including lizards, symbols of Alor. On average, Moko in the Kalabahi museum are

sixty cms high, have tympan diameter of thirty cms, with few smaller exceptions (H40/D25 cm) - several adorned with a strong rope to hang them. No sculpture on the tympan “if to be played” (Figs.

24-28) says the curator.

The other Moko main sites are situated on the next Pantar island (about two hours from Alor by boat), particularly in Kiria and Helangdou villages where several drums are generally stored in

attics and supposed to be played during festivities. (Fig. 25)

Moko modern usages in Alor (October 2015 trip)

Moko are not put in tombs but mainly utilized as musical instruments for ceremonies, from birth celebrations to any life events (building a house for example), marriages of course, funerals, and

generally to help dialogue with “good spirits”, often in relation with water or rice. Their players are generally men entwining the drum under their arm and using the palm of their hands to

produce “happy sounds” as a kind of nice “tam-tam”. Property of the family a Moko can be “prayed to” at any time and for any domestic reason, with lighted candles eventually, at least once in a

year for the main festivities in july. They are never displayed but kept securely under the roof with others values, inherited through generations and no longer sold except in case of

necessity.

In all aspects and for all religions, Moko drums remain highly regarded in Alor where women speak generally with emotion of their bride’s gift, if not bride-price, till to give them a “Papuan

kiss” with their nose as they may do with any parent in everyday life. Indeed Moko happened to find a “niche” of their own right in Alor modern society.

To summarize: Moko traditions survive in the small Alorese archipelago but are much less important as encountered by Cora Du Bois only eighty years ago and certainly very different from the old

unknown rites when Moko were created in connection with Pejeng drums apparently ignored in Alor. May be this unique survival was, as often said, the result of large isolating distances but so

many similar spots exist without Moko(s). May be it was the consequence of colonial times’ frontiers when the Portuguese and the Dutch proscribed the exchanges of Moko drums to avoid any “false

money” used in their territories, pushing inversely a strong and perennial appetite for them.

In any case for a Moko’s lover the trip to Alor, nice people but mosquitoes included, is a must.