China

Southern China did not exist where the Bronze Drums’ story began around 500 BCE and neither did Vietnam or other southern modern Nations meaning that, if archaeological findings are key, we must try to know their political early context to understand them. We are facing paradoxical situations in which bronze drums (TongGu in Chinese) were probably first produced and developed inside a mosaic of autonomous and obscure kingdoms fed by their river’ tributaries around the Red River Basin, not yet divided between China and Vietnam nations both claiming their paternity today... reasons, among others, to remain unassuming throughout...

In present-day Yunnan and Guangxi, the two principal Chinese ‘future-provinces’ involved, it so happened that a central power did not govern until 111 BCE, when Han dynasty invaded also the northern geographic area of present-day Indochina, and first Vietnam at the east before also a portion of Laos and Myanmar (Burma) in the west.

First described below are the (present) Yunnan discoveries from the end of BCE, and their succeeding (present) Guangxi and provinces around from the beginning of ce; even if links existed necessarily between these two entities also strongly connected via the Tonkin area in (present) north-Vietnam.

As a kind of prologue, guiding-marks could help us to better understand globally the environmental situation of these territories corresponding at that times to a kind of “hub” for south-Asian culture exchanges:

- Longitudinally, a lot of trails existed for a long time from the western Himalayan steppes to the eastern tropical rice fields down the sea to the southern islands accessible by land not so long ago before the rise in sea levels. Along this stretch of southern silk-road existed a lot of independent territories permitting, besides endemic wars, to share and upgrade tastes and inspirations.

- Latitudinally, the links became stronger with the emergence of Chinese centralized power giving birth to the first bronze cultures after neolithic under the first catalogued Empires (XIA then SHANG) based in Erlitou and then Erligan in northern Henan (Province). Travelling from Yellow River (Huang He) and Blue River (Yangzi) via other southern basins new gorgeous bronze pieces (vases/gongs/never drums at that stage) might have inspired casting techniques for “southern barbarians”. From its creation, Western Han central Empire (206 BCE/9 CE) decided to colonize the always turbulent but wealthy southern lands populated by so many ethnicities (future Nationalities) such as the Thais or Viets (Yue) and others. Negatively that colonization restrained local political freedom but positively it gave more opportunities for exchanges along the transversal Red River Valley and beyond.

Bronze drums in Yunnan

Yunnan province (390,000 km2) now bordered to the south by Vietnam, Laos and Myanmar, is an overland passage with a present population of 44 million: comprising 25 official ethnic groups (Nationalities). The Red River links the flat deltaic land bordering the gulf of Bắc Bộ (including Halong Bay (Vịnh Hạ Long) in Vietnam) with the wooded Plateau of Yunnan which means “south of the clouds” (Himalaya) comprising many water tributaries of the Red River Basin.

Until the finding of Wanjiaba (no. 23) tomb in Chuxiong (100 km NW of Kunming) drums’ discoveries could be repertoried in parallel with Heger’s classification giving anteriority to type I (mushroom), so numerous between northern Dianchi lake and southern Ma river irrigating Đông Sơn in Vietnam.

The Wanjiaba enigmatic case

In 2015, only a small official monument in a poorly-closed field gives an idea of the discovery in 1975 of four bronze drums giving birth to a “revolutionary hypothesis”. One drum being now in the Beijing National Museum and three in the Kunming Museums, dating back from Spring and Autumn period (770-476 BCE).

Seventy nine tombs where classified from the same cemetery with only one other similar drum (in no.1) after the no. 23 was found by chance by a peasant. That tomb was about ten meters under the earth, and measured six meters long and two meters high. A skeleton was inside a huge wood-coffin 2.6 meters long, containing 577 articles of different materials, mostly in bronze from bracelets to axes, with drums outside and apparently under the coffin.

Two characteristics are striking after the first (Chinese) analysis:

1. The apparent good conservation and the tomb’s age from the (radiocarboned) coffin-wood even if the large tree trunk could well have been older than the burial itself, suggesting at least a fifth century BCE date. Consequently most scholars, Vietnamese apart, agreed that these Wanjiaba drums, displayed in many museums now, were likely to be the oldest casted up before any Heger I and the first “drum craddle” known to today. Looking much more like a reversed kettle giving birth to a drum: progressively strengthened and properly decorated: a revolutionary scenario indeed.

2. Pending new data, the rustic Wanjiaba drums detailed below could be the prototype, not yet decorated first, of the bronze drums to be found all along the Red River Basin, Đông Sơn (Heger I) type included; an hypothesis not welcomed in Vietnam where Wanjiaba had been assimilated to late Heger IV type from the beginning of ce Measuring from D25 to 40 cm and H25 to 35 cm, Wanjiaba drums were dense like kettles, first without apparent handles and decoration, one small bulb in the tympan-center becoming soon a “star” on next items with handles. On the top and on the mantle soon existed relief lines or band of meanders or spirals or amphibian patterns with incised designs. They were rich in copper, up to 99%, an abundant ore in Yunnan even if no drum’s casting sites were found there up to now, with at least 1% tin.

Named Wanjiaba after their first place of discovery doesn’t mean that these drums were created in Chuxiong... others were found far away in Yunnan province. Their rustic aspects can match the idea of creation from pre-existing kettles instead of imitation of pre-existing wooden drums...becoming in fact a synthesis of both.

Wanjiaba and next rustic bronze drums (Fig. 3) opened the door to coming Dian ones, varying from Heger IV to Heger I types, wearing geometric and figurative decoration with fauna or flora, and figuring clearly a drum and no more a kettle.

Dian and other ‘pre-Chinese’ Kingdoms

Dianchi Lake, near Kunming, is famous for its vastness (40x10 km) on Dianzhong Plateau (alt 1800m). Via the nearby Lishe River it could be linked to Erhai lake (near Dali) in the north and, via the southern Yuanjiang (Red River) Valley to Bac Bao. That central situation, between the equestrian cultures in the north and the rice field cultures in the south, probably corresponded to wealthy kingdoms harboring the oldest local bronze drums productions. Of which Shizhaishan hill on the Dianchi Lake with some twenty tombs discovered around 1960, was the cemetery of the Kingdom of Dian before the Western Han colonisation. Also-known as Barbarian by the Han, the Dian civilisation of farmer-stock- breeders was in fact very sophisticated as seen on their bronzes including cowry-container and drums illustrating the importance of livestock (horses/cattle), the nice forms of habitat and dress, the war customs, an aristocratic taste for adornment, an entirely animal repertory both symbolic and decorative, a feeling for combinations of geometric patterns too.

We do not yet know the origin or the pre-mature stage of this culture apart from its ‘steppic’ influences. It was certainly very complex combining agricultural and metalworking techniques and the exact spread of the Dian civilization remains difficult to delineate. May be existed at the end of the first millennium BCE a sort of “Red River cultural confederation” comprising at least two hubs: near Shizaishan (in future south Chinese Yunnan) and Đông Sơn (in future northern Vietnamese Tonkin), an hypothesis corroborated by the presence of bronze drums from both origins in both centres. At their pinnacle these cultures probably suffered under the impact of the coming Iron Age and colonization of northern Chinese Han which apparently stopped their production of bronze drums after the first century ce, Guangxi taking strongly the baton.

In the Shizaishan Dian Royal tombs, as in Lijaisan or other famous necropolis of the province, basically three types of “kettles” bronze artefacts were found:

(a) So called bronze cowry-container (of which cowrie-shells) the most spectacular and original not found elsewhere. Even if not drums basically, because impossible to play, these containers “set

the tone” of Dian’s civilization; meaning that we must look at them briefly before turning our attention to the drums themselves.

(b) Local (Heger I) bronze drums at least casted in three pieces–one for the tympan and another bivalve for the mantle–like the cowry-containers with which they shared part of their decoration

from a common equestrian and hills origin inspiration.

(c) Đông Sơn bronze drums (Heger I) coming from the south of the Red River Valley (future northern Vietnam) wearing slightly different

decorations in accordance with their more tropical sources.

In the huge new Yunnan province museum (YPM) in Kunming was made a suggestive presentation of early drums and kettles giving a good idea of their similarity and probable relation at the verge of Spring and Autumn and Warring States (475-221 BCE) periods (Fig. 4)

(a) Cowrie shell containers from Yunnan (Shizhaishan; Lijiashan; Tianzimiao etc.)

From about one hundred cowrie containers recorded, 40% are in the form of a barrel, 40% in the form of a drum (even if not playable due to figurines on top), the others are in between. Generally they would permit the protection of valuables put inside, often cowrie shells, shells being one of the most precious items at that time. In brief, they are composed of a cover with high-relief humans or animals casted apart and a body with often three to five small supporting legs and lateral handles, either tiger-shaped or not. Advanced casting techniques were necessary from basic clay to piece-molds; the handles, openwork plaques, sculptures on the top, being made apart. The results were gorgeous and remain unique in mankind story (Fig. 5).

Symbols of wealth, only found in royal or elite tombs, cowrie containers probably came from kettles. From the Warring States period they helped to improve drums’ casting and decoration with animal or human sculptures or designs. Some drums were transformed in cowry containers with figurines added on top but also existed double pieced drum container (Fig. 6). In total a wide bronze family but only the pure drums were musical instruments and largely spread, and therefore must be distinctly considered.

(b) Bronze drums from Dian royal tombs

From Shizhaishan burials, bronze drums appeared in different ways:

1. Either lined up or piled up they are basically musical instrument and sign of power, attested sometimes by a sculpted figure beating a drum with a mallet. The peaceful or warlike sceneries

shown on the bronzes of Dian, were linked to agricultural works, and funeral rites.

2. Insignia of power and prestige reserved for the elite and probably magically-endowed, bronze drum, designs are both as a testimony of present life and other worlds.

It would be risky to state more dividing lines that our fragmentary knowledge can lead us to imagine. At least are demonstrated the bronze levels of beauty and complexity from the third century BCE in Yunnan.

Dian tomb drum (Fig. 7) wore a central star (10 rays here) with a large band of big birds on the tympan encircled with geometric bands (no frogs) and a large rank of riverboats with rowing people on the mantle between geometric bands. Four handles but nothing sculpted on the pedestal (Warring States period/475-221 BCE).

Drums that were unearthed in Shizaishan (Jinning county) are regarded as the standard samples of the Dian type (Heger I), often similar to Southern Đông Sơn (Yue) type meaning probably a lot of interchanges: the convex superior part of the mantle is also larger than the tympanum but the foot base is smaller and relatively high. Most of the drum’s decorative patterns are realistically done: the main band on the top had flying birds like egrets; the main band on the chest is decorated with some people rowing boats; bands are often striped with vertical lines which were further divided into rectangles decorated with pictures of panels, plaques or cartouches; but never showed, on the contrary of Đông Sơn ones, people adorned with feathers. On some were oxen or was depicted an ox-killing ceremony, another sported a stag or a tiger probably originating from steppes backgrounds... No frogs during the first period but they appear progressively from the early Warring States through the beginning of the East Han dynasty beginning ce, a period lasting about 500 years in total.

(c) Đông Sơn drums found around Dianchi lake but cast in the south (future Vietnam)

Dian tombs contained several Đông Sơn drums but the opposite is also true: Dian drums were found with local ones in burials in the north of Vietnam, of which one in Dong Xa, Hung Yeng province at the verge of BCE/CE. Demonstrating again how the Red River Basin was a drum community, not excluding northern or southern specificities but not necessarily as conflicting as imagined by any nowadays. For sure positive win-win challenges resulted from the comparison of decors or different ways of casting and the usages were adapted to sub Himalayan or sub tropical situations.

The respective decorations help to make the difference between Dian and Đông Sơn drums: animals (horses versus buffaloes), bird species (from sea versus continent), are not the same in the littorals or in the hills. The best artists were possibly recruited here and there at few hundred kilometers of distance along the Red River valley, respecting diverse tastes or ways of casting but certainly exchanging a lot. Cowrie shells are a typical Dian way which does not occur in the Dong Son culture burials but the basic concepts and drums’ architectures are near-identical, all being part of a comparable “visual system”. Đông Sơn drums turned upside down became sometimes cowrie shells while cask-shaped containers could be converted in drums after rubbing out their figurines atop, in brief a kind of Red River Valley “ballet” (“pas de deux”) if it can be said.

Note: Northern bordering provinces (Sichuan; Guizhou...) contained also drums but not as numerous as in Yunnan from where they probably came.

Bronze drums in Guangxi (and adjacent provinces of which Guangdong)

Until recently more than 75% of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region population (46 million on 236,000 km2) was not Han after two millenaries since the colonisation. Astonishingly, bronze drums history began in Guangxi when it ended in Yunnan, around the verge of BCE/CE, to be pursued until modern times if we consider the persistent drums players, mainly Zhuang, Yao, Miao, Dong and Yi peoples.

Guangxi is connected with western Yunnan by the long Pearl River originating not far from Dianchi Lake but had probably closer relations with Yue (Viets) in future Vietnam, another Han colony near the Red River Valley delta with a common sea gulf (Gulf of Tonkin/Gulf of Bac Bo). Drums found in southern Archipelagos or along continental Indochina came either from Guangxi or Đông Sơn, even if more studies must measure their respective importance.

A biography of Han general winner of Viet Trung sisters revolt (40 ce) said that it took bronze drums from Yue people when it conquered Jiao Zhi (Guangxi). During the Tang and Song dynasties (7th-12th ce) bronze drums were sometimes offered by Nationalities to the Imperial court (Ling Wai Dai Da and Man Yi Le Zhuan records). From the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 ce) countless references were made to bronze drums, about their discovery or production involving social customs. In 1799 Qing Dynasty (1644-1912 ce) governor had a pavilion built specially for the bronze drums, etc. Unlike in Yunnan, drums were never forgotten in Guangxi, continuing to be built and played.

A selection of the Guangxi documented drums, not far short of one thousand in total with always new discoveries, can be seen in Nanning’s huge new Guangxi Nationalities Museum or in the old City Museum. The Chinese had named too many categories after the place they had been discovered; the most numerous are, in order, called Majiang; Beiliu; Lengshuichong, the last name often being given to all Guangxi drums types by Westerners due to over-simplification. The Vietnamese distinguished them differently under their own “Đông Sơn umbrella” classification but, grosso modo, the Heger I type equals the Lengshuichong (as also the Shizhaishan in Yunnan); the Heger II equals the Beiliu (and Lingshan) types; the Heger IV equals the Majiang (and Zuny) types; and Ximeng (minority) items are not far from Heger III.

Astonishingly, compared with the great number of recorded drums, no big centres of production were discovered until now in Guangxi where all the necessary ores existed to produce them. The welcoming Professor Li Fuqiang (Guangxi University for Nationalities- Nanning) is working with an open-minded team to fill this gap and also to evaluate other existing bronze drums abroad, related or not to the Guangxi productions through the ages.

Note: Very few drums of the Shizhaisan type were found in Guangxi, no Wanjiaba up to now. On the contrary the drum’s relations between Guangxi and Tonkin were probably stronger, the Heger II types being largely spread. It was, and it remains, much more easy to travel by earth from Nanning to Hanoï than to Kunming, much less kilometers and hills.

a) Majiang drums (Heger IV typed)

Named after a drum unearthed in a tomb in Guidong railway station (Majian County), its shaped characteristics are generally small and flat. The diameter of the slightly extended tympan is smaller than the chest divided into two parts by a protruding edge. Most of the drums bore pictures of animals, plants, people and houses; during ce the main pattern is a waving flag with some animal or ancient character symbols, for example there are some titles or dates from the emperors, or some words for good luck. The distribution of this type is very wide (about 300 were documented); its typical frame with inscriptions began with the south Song dynasty and encompassed Ming and last Qing dynasties, continuing occasionally to be used by Zhang, Miao, Yi and few other nationalities.

b) Beiliu drums (Heger II typed)

The large diameter of their tympanum measures from 50 to 165 cm (average 70 to 100 cm) and the shape of their bodies is thick and heavy.

Their faces were larger than their chests, slightly convex as the waist appeared concave with two pairs of circular handles attached. Four (or six) frogs or other high-relief animals stand on the tympan with a protruding central star, often with eight rays. A Beiiliu type drum is divided into bands by fine circular lines on the tympan and the body, decorated with different patterns, geometric or not. Less than two hundred Beiliu are documented, cast mainly from the Western Han to the Tang dynasty (206-907 ce) and principally used by Wuhu and Li peoples. The biggest of all the northern drums was encountered near Beiliu (D165 cm, 130 kg, Fig. 15)

Interestingly, Beilliu and Lengshuichong types are presented conjointly (Fig. 10) in Nanning (GNM) from Eastern Han and Southern dynasties (220-589 ce). Respectively, at right Beiliu/Heger II type (93D/H53 cm) with in-relief frog; at left Lengshuichong/ Heger I type (83D/H60 cm), with in-relief frogs and horses and stars in both cases.

(c) Lengshuichong type (Heger I typed

Named after a village in Tengxian County their shape is high and large, relatively thin and light. The highest diameter of the chest often exceed that on the tympanum covered with frog figurines (generally four) with horses, riders, oxen, ducks, tortoises, birds, fishes in between etc. The main patterns are bands of egrets or boats or dancers figures with bird feathers on the tympanum and mantle. On some of them horses with their rider might replace the traditional frogs, a reminiscence of steppes influences and maybe the “mountain spirit” represented by the “golden horse” so well depicted on Dian bronze containers. More than one hundred Lengshuichong (Heger I typed) were recorded, probably made before Beiliu from the Easter Han through to at least the Song dynasties. (Figs. 10-11)

Note: All Guangxi drums above are not far from their older counterparts even if boats formats or other motives or geometric patterns can vary. But the main difference is that they continued to be nicely developed long after the disappearance of the Dian and Đông Sơn drum cultures; they were also sent to all (future) Indochina and in southern Archipelagos. Any strange practices, not fully explained until now, are shown in some burials in Xiling (west Guangxi province) where many drums were cut and assembled in “Russian- doll- like- fashion” mixing Đông Sơn and Guangxi drum types. In Vietnam only some mountainous ethnics people like Mường continued to use drums, Heger II principally.

A GNM masterpiece (Fig. 11) wore three types of in-relief animals (frogs, horses, dogs) associated on the tympanum covered with a twelve rays star. Other originality, the presence of two double perforated ankles added with two small ones covering fully the mantle. It must be admired the beautiful results during a long period as demonstrated (Fig. 12) by a comparison between drums from successive Song and Ming and Qing dynasties.

During near two thousand years Guangxi people was able to find customers (in China and abroad) and to maintain a good level of casting using apparently the same basic techniques first developed by Dian and Đông Sơn. For the very big pieces, as shown in GNM, five moulds were utilized, four for the mantle and one for the tympan, the in-reliefs decoration on the top being casted separately, piece by piece and added.

Last masterpiece to be seen in Nanning City Museum: a big drum (D80/H50 cm) from possibly the last Eastern Han dynasty (before 320 ce) featured the best of early Guangxi Lengshuichong production. Four big toad figurines (one missing) on the tympan are incorporated with charming groups of three small mice bearing a baby on their back. A central twelve ray’s “star” is surrounded with rows of big birds and dancing people and geometric circles and designs. The same decorations are repeated on the mantle with six pierced handles (two missing). Despite small failures, a supremely elegant piece with nice imaginative characters. (Fig. 13)

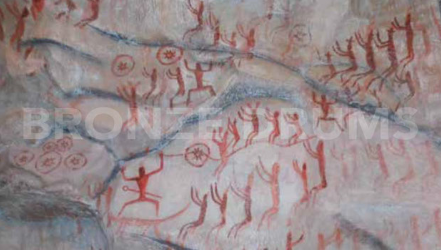

On a wall of the same Nanning City Museum were reproduced primitive paintings on which figure people (dancers? warriors?) with (possibly) encircled bronze drums. (Fig. 14)

Few Parting Thoughts

Some Chinese specialists were about to consider that the mid-west area of Yunnan was the “birthplace” of ancient bronze drums (Wanjiaba) up to more sophisticated ones and that Guangxi may be regarded as their “supreme headquarters” with a lot of varied productions during two and a half millenium in total. Even if the next chapter will reveal opposite feelings from the Vietnamese side.

Wanjiaba drums with a central star on the tympan probably initiated the formats but the other decoration designs came posteriorly with people mastering the necessary skills, coming from both Dian and Đông Sơn areas. Multi-pieces clay mold with wax techniques were utilized and one-piece lost wax often reserved to cast figurative “plaques”.

What is indeed impressive is the constantly increasing number of the findings and their unbelievable quality and diversity. For certain, Yunnan and Guangxi had played a key role in the bronze drums odyssey; even we must never forget the novelty of the present international frontiers, meaning the difficulty to speak separately of Chinese or Vietnamese hubs.

From the reported facts above, it is better to consider the existence of geographical clusters of culture first along the Red River Valley and its tributaries integrating Dian and Đông Sơn (Cluster no.1) and then chronologically Guangxi (Cluster no. 2), paving the way to distinguish in coming chapters other main clusters through the ages and places.

In any case we globally face “animist worlds” so perennial in Asia even after the apparent victory of “modern religions”. In that context: rain (fertility) and thunder (noises) played a fundamental role shared by all “bronze drums peoples”, friends or sometimes enemies but with common cultural backgrounds and important exchanges. It can explain the relationships existing between bronze drum techniques and decoration all along the Red River basin without necessarily national leaderships pending discoveries yet to come.

China dynasties chronology in brief

This chronology doesn't mention secondary sub-periods.

Xia 2000-1600 BCE

Shang 1600-1027 BCE

Zhou 1027-221 BCE

Springs and Autumns 770-476

Warring States 476-221

Qin 221-206 BCE

Han 206 BCE-220 CE

Occidental Han 206 BCE-8 CE

Oriental Han 8-220 CE

Six Dynasties 220-581 CE

Sui 580-618 CE

Tang 618-907 CE

Liao 907-960 CE

Song 960-1279 CE

Yuan 1279-1368 CE

Ming 1368-1644 CE

Qing 1644-1911 CE

Annex to China

Nationalities and bronze drum’s modern features

A.J. Bernet Kempers noted fifty years ago how the Woni of southern Yunnan, during festival rituals “beat drums until recently”... “They stick pheasant tails on their heads to dance, they are called those who disperse the spirits”... “It is possible that the drum scenes represent funeral rites, in which context the herons would symbolise longevity and the boat may be carrying away the dead spirits; but many alternative are possible, may be witnessing fertility ceremonies at the onset of the rains, or celebrations of victory in combat”...”the plaques (with scenes) on the bronze drums have been interpreted as armor or as purely decorative devices”.

Nowadays only survive ceremonies seem to less correspond to believers’ necessities than to reminiscences of bronze drums’ habits, if not pure nostalgia or folklore. Of which the seasonal festivals of “Barbarian Nationalities” (Yi, Zhuang, Buyi, Dai, Miao or Mường, etc.) in some southern China places including the “Guangxi drums’ festival”.

New perspectives had recently emerged, sometimes at University levels, with the creation of specific orchestras including bronze drums for part or in totality, with DVD or CD production output, in China first and sometimes overseas as in... U.S.A.! (Fig. 16)